Maps, Contemporary Landscape and the Bird's-eye-view: Part 1

Don't worry Mom. We're not lost, we're going somewhere else.

-Eric Manolson Lax, age 6

For many months I watched as my friend Ilana Manolson toiled to perfectly impose her artistic vision on a large installation that is currently on display in the Johnson Lobby of the Boston Public Library (BPL). This installation represents a year of vigorous exploration and risk-taking by a highly successful painter known for her lush, lyrical, abstract landscapes. Intimate and transcendent, her paintings pull us to the water's edge and hold us captive within the confines of the square frame of the panel. Mesmerized, we see only what lies before us. I think many people would wonder why she would choose to tinker with something that has worked so well. When I asked her about this, her response was fairly simple: the need to be relevant. Artists are the translators of the visual world. One cannot remain relevant while standing still. This means finding ways, whatever they may be, to push up against the boundaries of your own work, to walk away if necessary, if only to come back with fresh eyes and begin again.

1. Maps and contemporary landscape.

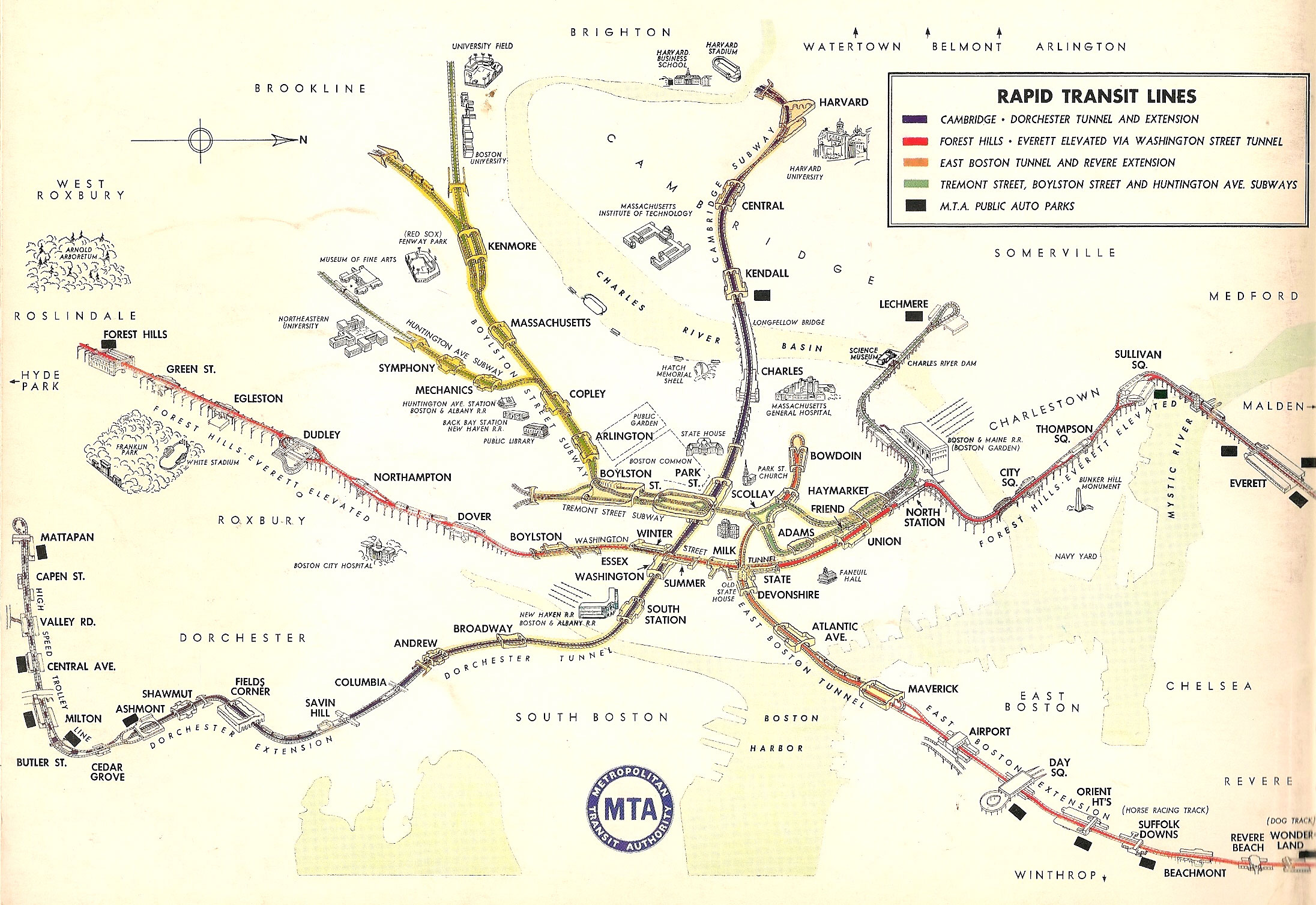

Ilana is a systemic thinker by nature. As such, it doesn't surprise me when this trained botanist gets enthusiastic over what to me, is just a pile of old maps. The BPL has given her access to it’s rare map collection. In many ways, botany, landscape painting and cartography have a lot in common: they all are ways in which to take a close look at the world and present it from a specific point of view. The roots, stems and streams of one are the subway and rail lines of another. Ilana was telling me how she became interested in maps during the past year's frequent travels, and how she was captivated by the exploration and the anatomy of place. Maps are abstract, she says, they give you a specific fixed point of view of a place, a singular system of connections by which to navigate within that place. But being there- well, is wholly different; it is personal and fluid.The more Ilana traveled the more she became aware of how place itself connects us  to each other, interweaving our various points of views and building layers of history. She began to envision her landscape paintings less as singular points of view (from the water's edge) and more as overlaying and expanding systems; roots woven with roadways and waterways connecting us to one another through our varied journeys.

to each other, interweaving our various points of views and building layers of history. She began to envision her landscape paintings less as singular points of view (from the water's edge) and more as overlaying and expanding systems; roots woven with roadways and waterways connecting us to one another through our varied journeys.

I see her studio filling by the week with more and more roots. She travels to a Boston arboretum to collect root balls, massive gnarled knots and serpentine branches. I see her struggling to reconcile her love of light and space she learned to render so exquisitely in oil paint, with the cacophony of earthy mass accumulating on the floor. This polarity of earthly and etherial is not unfamiliar to her as an artist. Over the decades she has addressed stasis and flux and the cycles of seasons many times. The problem she faces now is form, how to move from a flat, static canvas to a more dynamic medium that reflects the fluidity she feels when talking about layers of connections. As a result she must also make adjustments to scale and perspective.

As is the nature of systemic thinking, the idea of connections grew to include everything but the proverbial kitchen sink. One day I enter the studio to find large globes the size of exercise balls, composed of tubers, plaster and wire lying around the tables with smaller "chunks" scattered about in various states of paint. It looks like a sci-fi movie set. Ilana shows me a sketch of what looks like large suspended sphere exploding and raining down little worlds onto heads below. (actually, there were no heads in the sketch). I blame the size and specificity of the installation site itself coercing her into such an impossibly bold visual statement. The Johnson Lobby at the BPL is anything but intimate. The space is interrupted by multiple doors, desks, glass and metal detectors. A balcony and display case bisect the one and a half story stone wall where Ilana's piece was to hang. Ilana was still coming to terms with new materials, structures and techniques she was developing during her year long hiatus. Suddenly, integrating untested three-dimensional plaster forms, oil painting, photo transfer processes AND the roots themselves was only half of the challenge. Site installation issues kept rearing to divert the progress. Her vision was running away from her. She wasn't able to harness it until she could force herself to step back and approach it again with the mantra scrawled on her studio wall:

simplify

focus

let it rip

Some artists (like me) can't seem to pull back until its a full blown FEMA disaster. Bless the artist who can extrapolate and salvage and file that idea away for another time when the troops are well fed and readied.

Next post: Part 2. The Birds-eye-view. The installation completed.

This installation is presented as part of reThink INK, a collaborative exhibition produced by the BPL and Mixit Print Studio celebrating the studio’s 25th anniversary. The exhibition features over 150 works by 71 artists and runs through July 31st at the Boston Public Library, Copley Square.

Labyrinth of Vision

"Start at no particular time of your life. Wander at your free will all over your life; talk only about the thing that interests you for the moment; drop it at the moment its interest starts to pale."

-Mark Twain, in 1904, about his method for writing his autobiography

I have been trying to read the behemoth Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1 since December 2011. Has anyone really read the whole thing? Then again, maybe that is Twain's point. Life isn't chronological. It only appears that way to us when we are staring at a calendar. So any reflection on one's life should not be chronological. But 3 pounds? The book weighs 3 pounds! That's a lot of wandering.

I have been thinking about this wandering thing and art. The old saying "a picture is worth a thousand words" pretty much means "feel free to wander at will, without the linear restrictions of text." I have been thinking of this a lot lately:

Wandering is critical to the development of vision and essential to growth in general. But what happens when vision exceeds means and capabilities? How do you manage a vision that drives you, and gives you life but has grown complicated with external barriers and internal tangents? There is a common acknowedgement among artists that we are always chasing the vision, no piece ever feels finished, rather it is just the beginning of another. It is often easy for us to get so lost in the hugeness of an idea, we fail to distinguish the parts. I have made my share of Frankensteins - that is, a complicated piece that really should have been several pieces.

Wandering is critical to the development of vision and essential to growth in general. But what happens when vision exceeds means and capabilities? How do you manage a vision that drives you, and gives you life but has grown complicated with external barriers and internal tangents? There is a common acknowedgement among artists that we are always chasing the vision, no piece ever feels finished, rather it is just the beginning of another. It is often easy for us to get so lost in the hugeness of an idea, we fail to distinguish the parts. I have made my share of Frankensteins - that is, a complicated piece that really should have been several pieces.

This has been resonating with me as I have been watching my friend Ilana deal with this very issue as she was working on her Boston Public Library installation. It's an imposing site to put art in and fraught with installation issues. Over and over I saw her adjust, re-evaluate and change coarse while staying true to her vision, but in the end it is still the product itself which will be evaluated. Sometimes adversity and sudden game changes suck the life out of an idea, yet sometimes it produces a more articulate, provocative and most importantly, honest art.

Bits and Pieces

"I am the proprietor of the Penguin Cafe, I will tell you things at random."

- Simon Jeffes, founder of the Penguin Cafe Orchestra

Penquin Cafe, Orchestra Music for a Found Harmonium

Music un-clutters my mind. It opens up space for all the bits and pieces in my head I have collected while working, driving and doing all those things I must do when not at my studio. Music brings my thoughts into sync and moves creativity forward.